RoboCup JR - Rescue Maze

Overview

In 2017 I participated, together with other three students from my high school — Daniele Gottardini, Alessandro Foradori, and Loris Gjini — to the international RoboCup JR competition which was held in Nagoya — Japan.

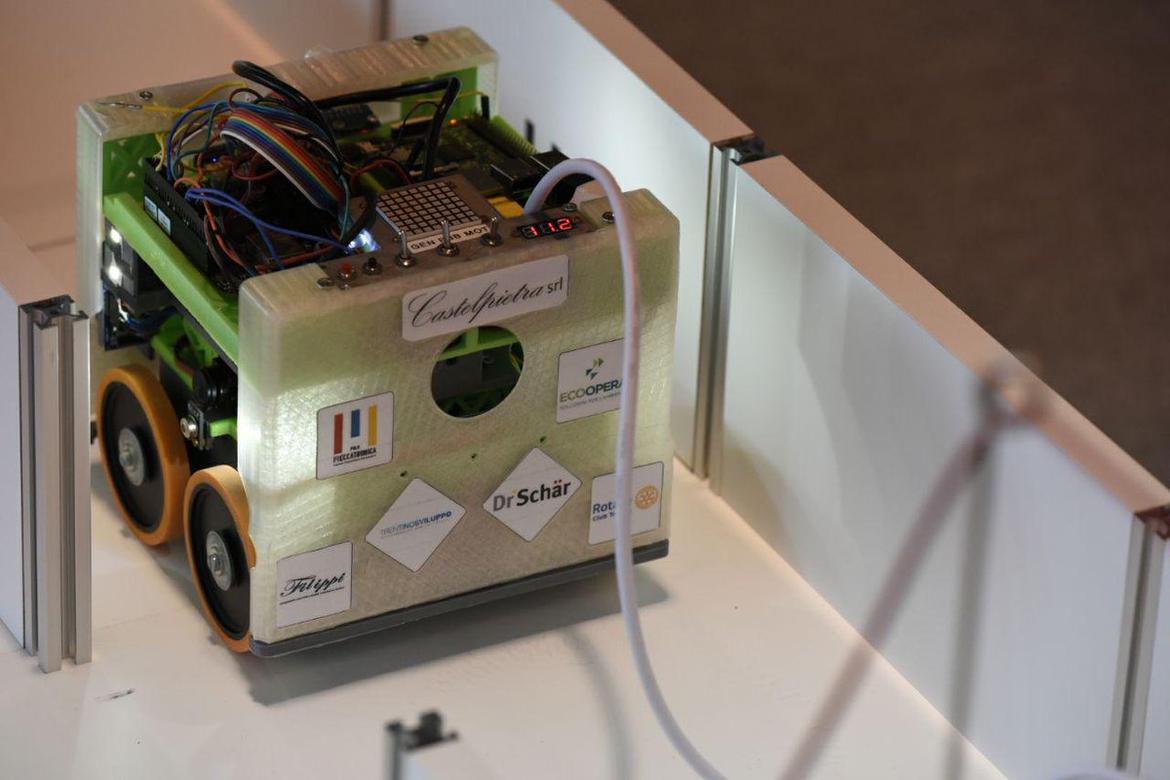

The robot which we brought to Nagoya for the RoboCup JR International 2017.

The motivation behind the competition was the simulation of an autonomous rescue effort in an unknown area which is considered too dangerous for human intervention. The rescue party (the robot) needs to be able to navigate the environment avoiding dangerous areas, navigating obstacles, searching for victims, and either rescuing the victims or dispensing rescue kits to them when found.

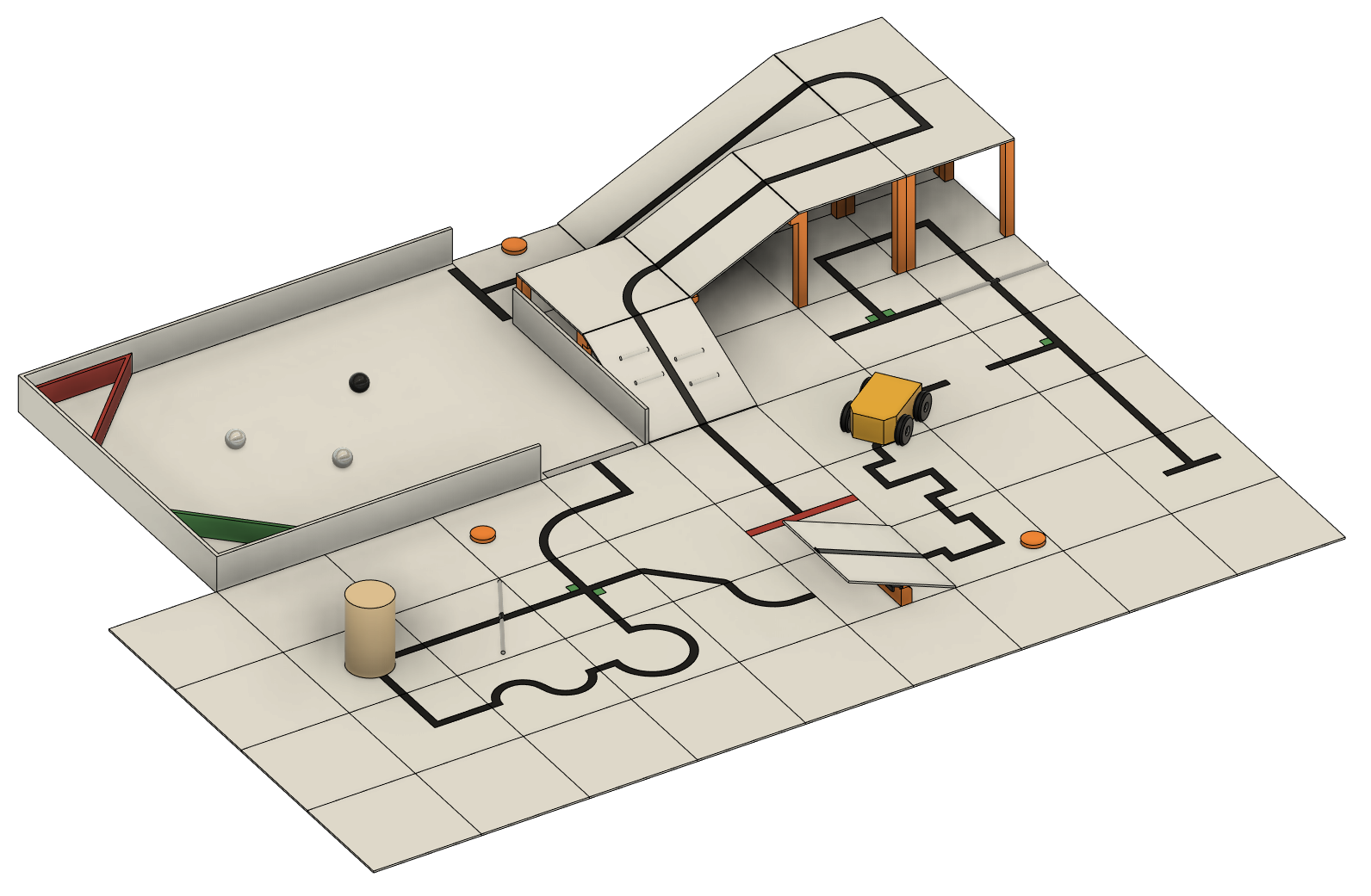

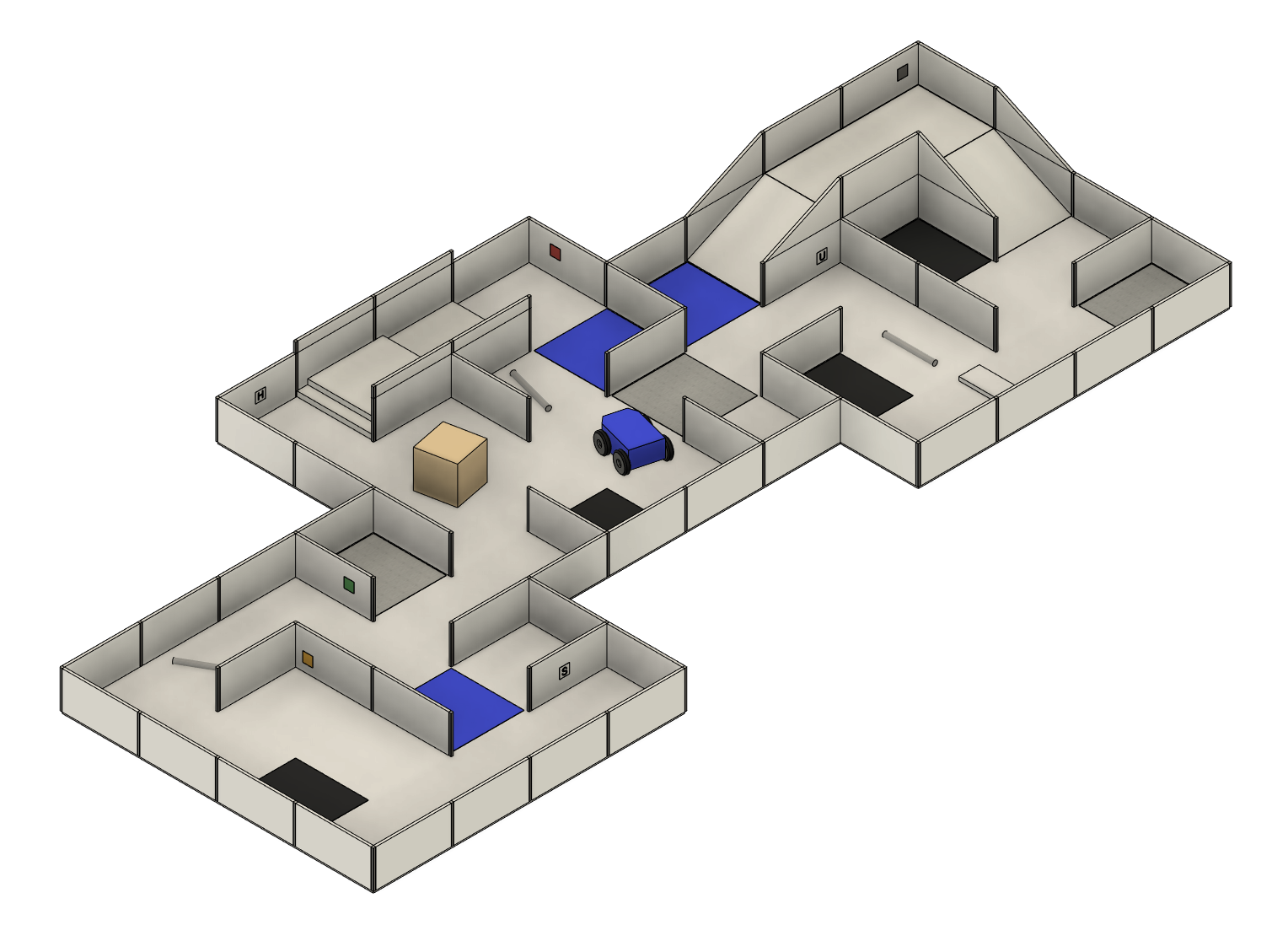

The Rescue competitions were divided into two categories, for which every team is tasked to build from scratch an autonomous robot able to perform a certain number of actions. In Rescue Line the robot needs to follow a line, navigating intersections and obstacles, and ultimately move the victims to a safe location. In Rescue Maze the robot needs to explore a maze, avoid forbidden areas, navigate obstacles, and dispense rescue kits to the victims.

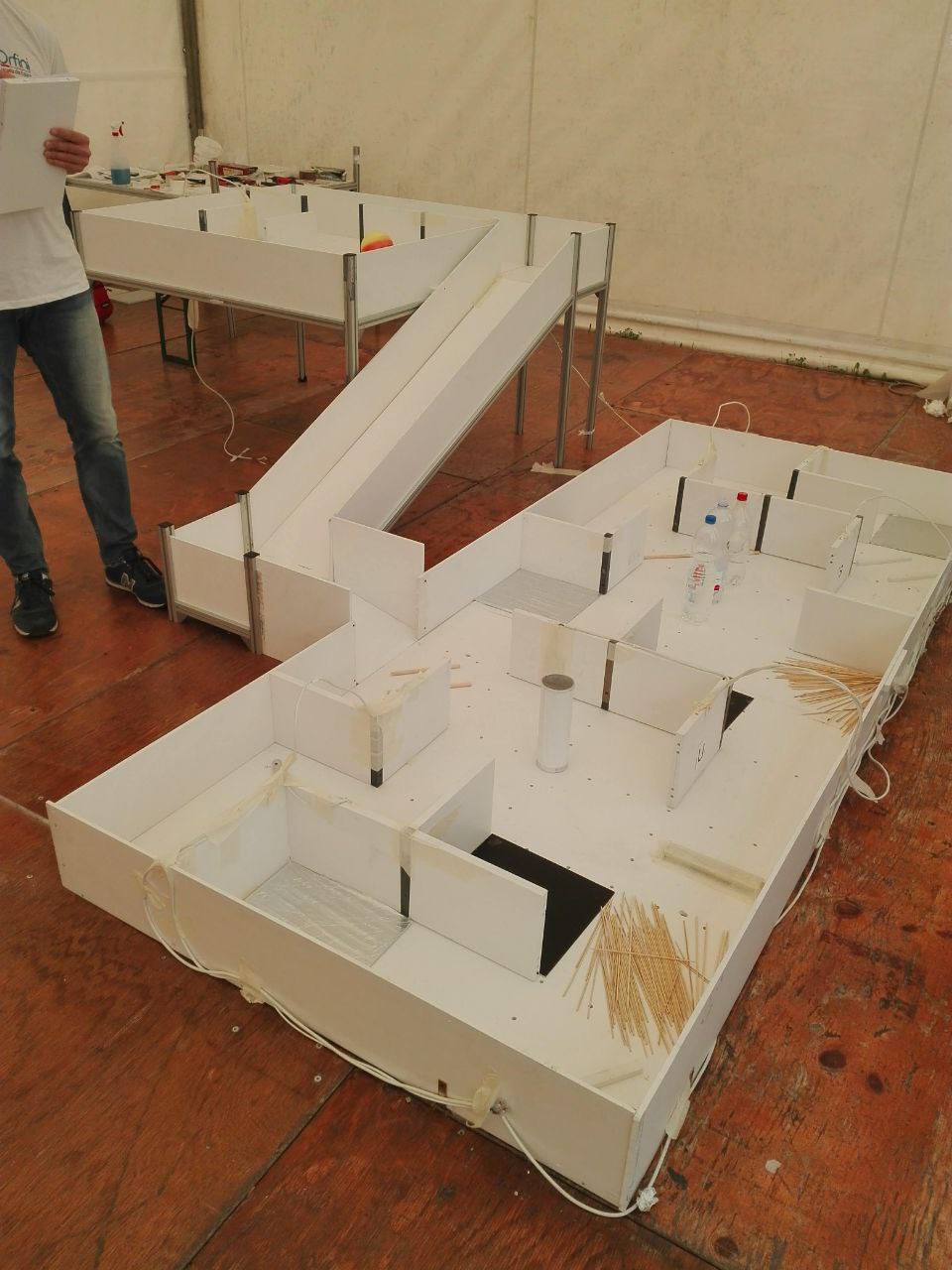

Rescue Line arena.

Rescue Maze arena.

Background

While in high school I joined several extracurricular activities, among which my favorite one was probably the school’s robotics club — a bunch of nerds hanging out once a week for a few hours, playing around with electronic components, 3D printing, and programming. The whole activity was organized under the supervision of Andrea Cristofori, a passionate lab technician who organized the whole thing and taking care of the “adult stuff” while enabling us to grow in an inspiring and stimulating environment.

The activities revolved around several projects, depending on the individual interests and needs of the participants. Some wanted to build small devices to automate repetitive tasks, others wanted to build their own drone from scratch, and some just wanted to tear down everyday consumer electronics devices to deeply understand their inner mechanisms. The main focus of the club was however the RoboCup JR Italia competition: a national competition taking place in the month of April or May each year, where teams from all around Italy meet up to compete in who is most capable in building an autonomous robot under a specific set of rules and constraints. The main prize is admission to the international level of the competition, and the honour to represent the country on the international stage.

During the school year we then devoted most of our efforts to designing and building a robot for the competition, learning valuable skills in the fields of 3D design and 3D printing, electronics, coding, and teamwork.

In the school year 2016–2017 we probably bit off more than we could chew in terms of ambition and decided to redesign the robot from scratch, leveraging experience from previous years. We sat down to brainstorm the solutions and design choices we wanted in our new build and designed the first iteration of what we eventually competed with at the national level.

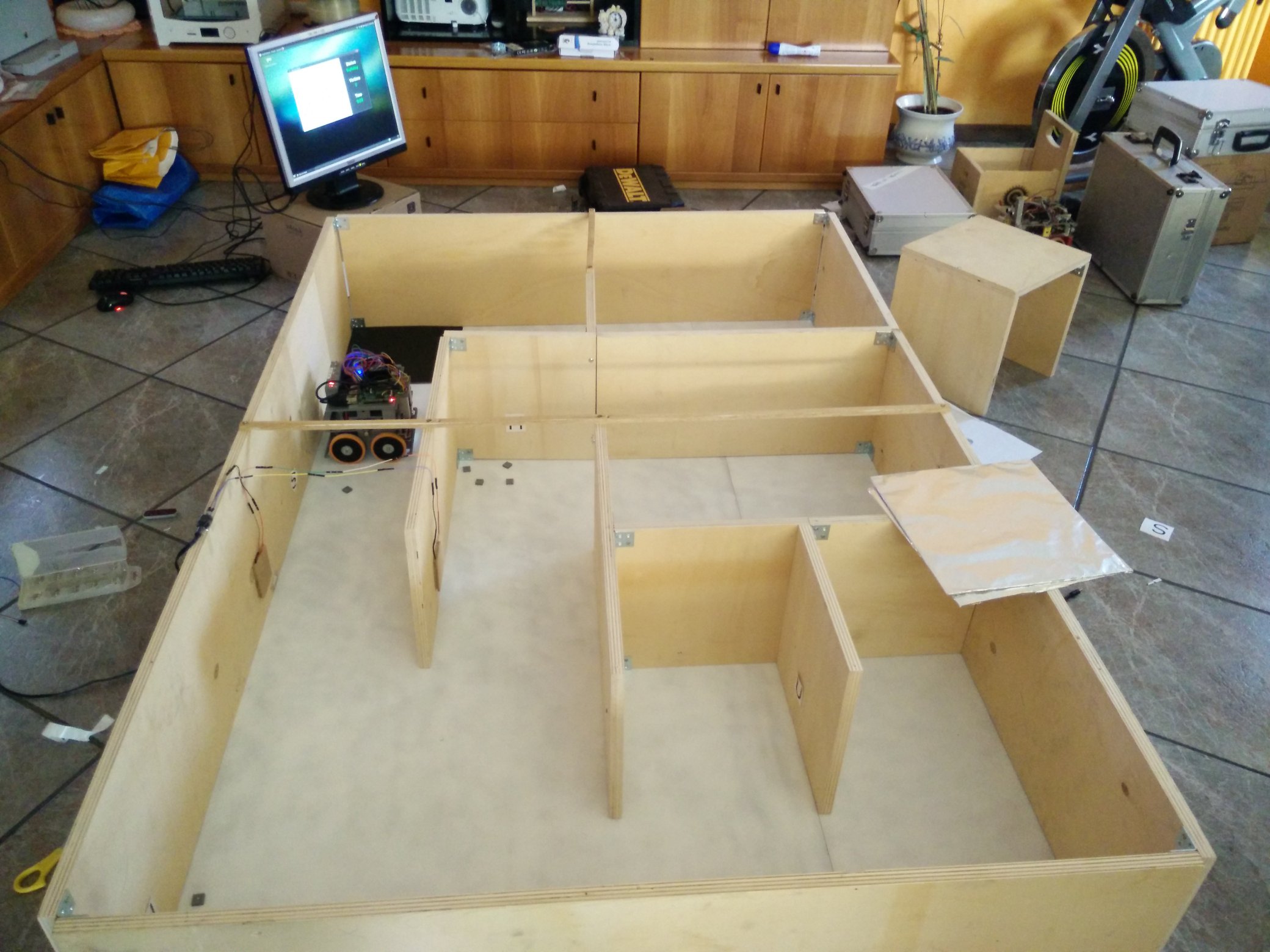

The final result had to be a fully autonomous robot able to explore and map a maze, and ultimately find and “rescue” the victims. In the 2017 edition the maze was made of 30 cm × 30 cm tiles with potential walls on the sides. The floor surface was not smooth and could contain obstacles, bumpers, ramps, and small steps that the robot needed to navigate, making solid mechanics essential. The victims were located on the walls and were represented by one of two different features: either a heated pad that the robot needed to sense using a heat sensor, or a letter printed on the wall that needed to be recognized using a camera or some other “vision sensor”.

Our robot

During our initial brainstorming we came up with many needs and wants, among which:

- Linux-based project rather than microcontroller-based

- Efficient maze-exploring algorithms (Dijkstra’s, BFS, A*, …)

- Custom diagnostic and monitoring tools with GUI

- Modular design with custom PCBs

- 3D printed chassis with mechanical suspensions

Let me go through these points one by one.

During the previous years we had experienced building robots based on Arduino, a simple open-source single-board microcontroller which can be programmed with its own programming language, which was close enough to C++ to make the learning curve not so steep, as C/C++ was part of the ordinary curriculum at our school. Arduino is an extremely cheap board, especially if using a Chinese knock-off version, which can take quite some beating without frying. It was perfect for learning the basics, but it had also many limitations. The biggest limitation, which we couldn’t work past, was memory. It simply did not come with enough onboard memory to store the information of the maze and running our search algorithms. We discussed several solutions, among which using an SD card to store and retrieve bigger chunks of memory, but ultimately decided to just go for another board.

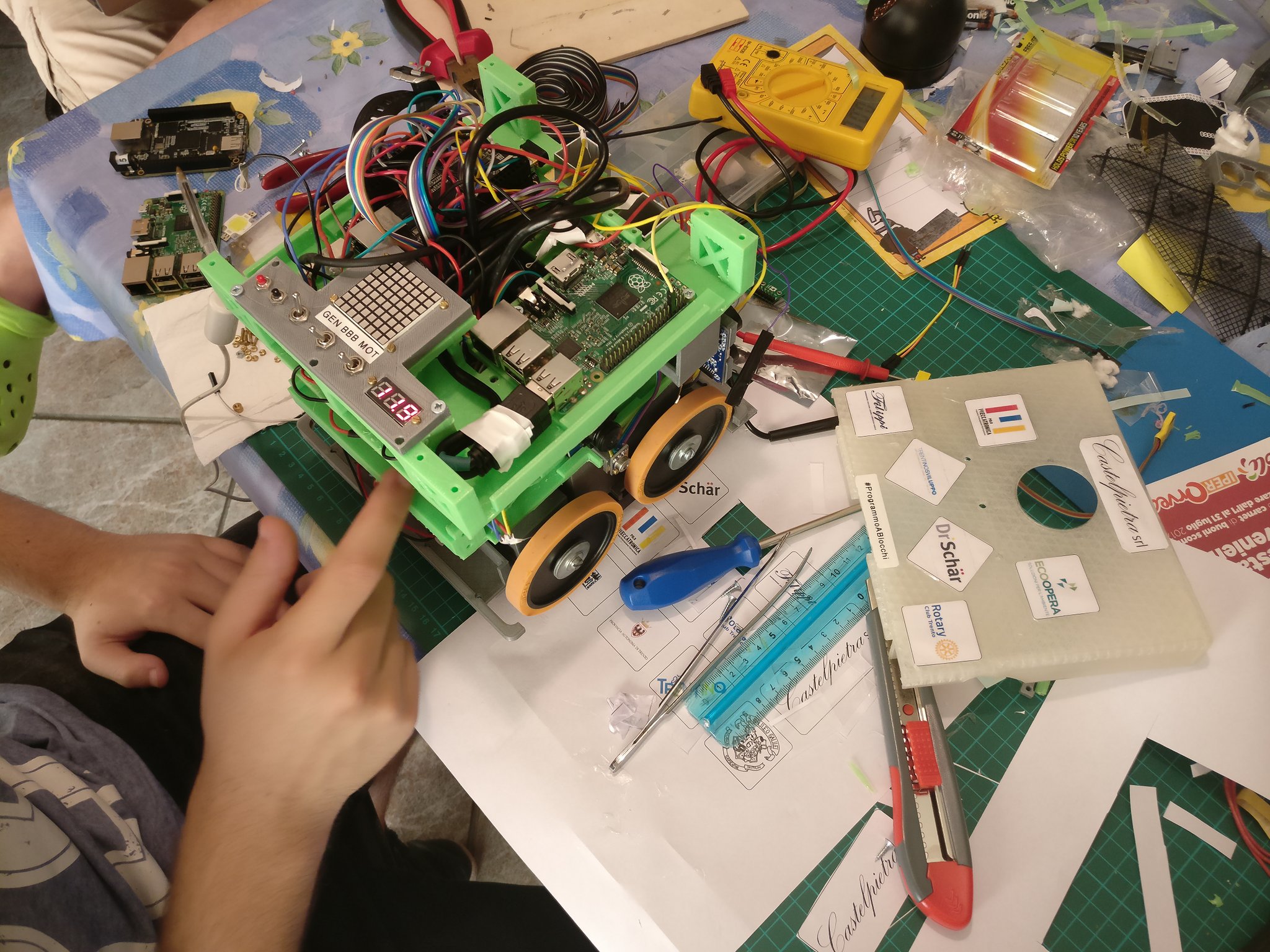

The popular Raspberry Pi board was very appealing, but it also came with its own set of limitations — notably the lack of real-time capabilities we needed to control some sensors and actuators. Looking back, we probably could have made it work by delegating the real-time tasks to an Arduino-based board, but at the time our eyes hovered over the BeagleBone Black boards: Linux-based boards with onboard Programmable Real-time Units (PRUs). Exactly what we needed.

Now that we had hardware capable enough to store all the information acquired about the maze in an appropriate data structure, we had to design our search-and-rescue algorithm. Ultimately, we opted for a simple algorithm that mixed a greedy approach with Dijkstra’s algorithm. We represented the maze as a graph whose nodes are the Cartesian product of maze cells and the robot’s possible states. Edges correspond to actions and are weighted by the time required to execute the movement and by the risk of getting stuck. Planning a path from one cell to another therefore meant running Dijkstra’s algorithm to find the sequence of movements that minimized time and risk.

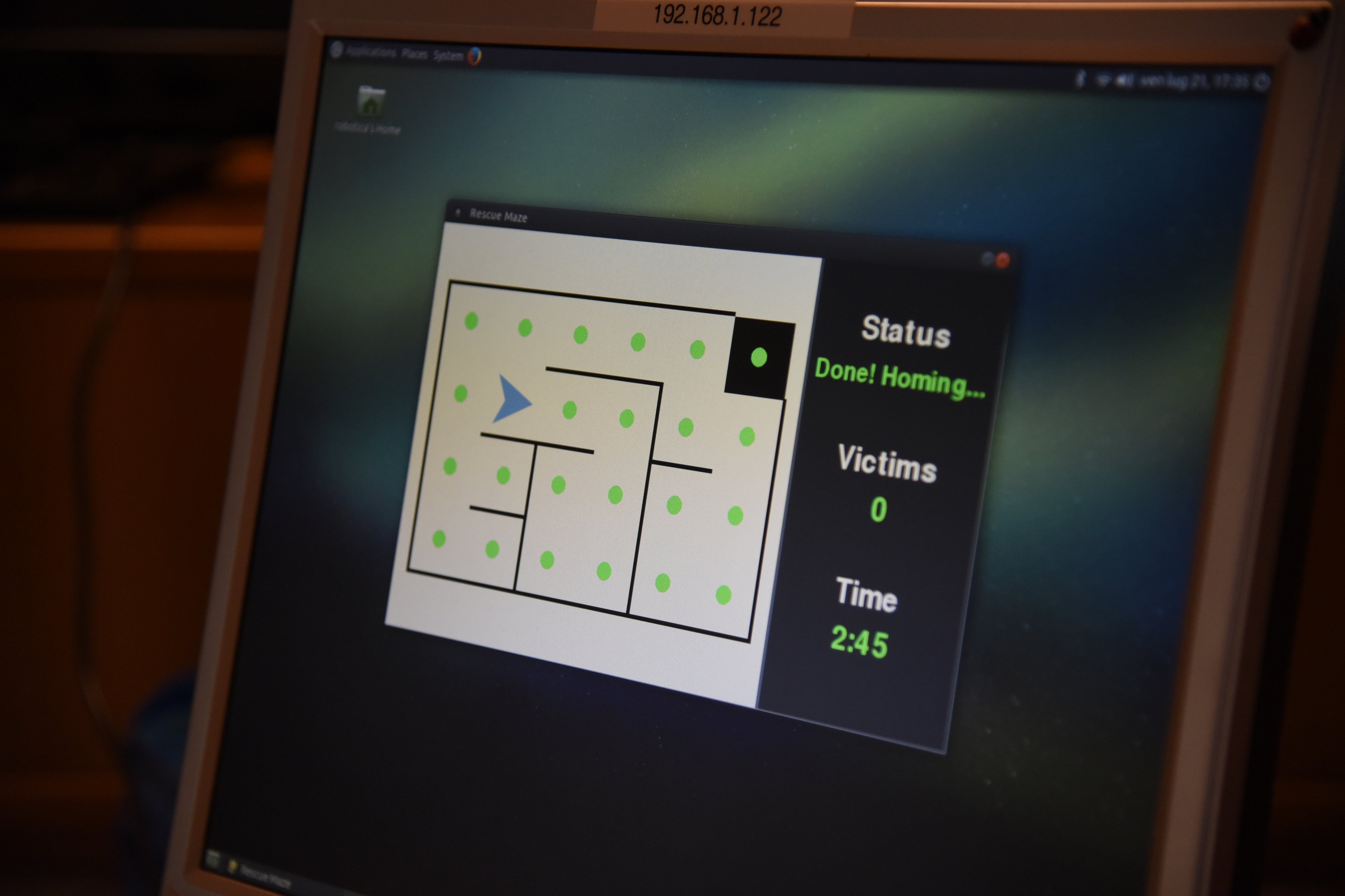

This was easier said than done. Actually, after ironing out the bugs, implementing the algorithm was straightforward. In practice, however, running the algorithm based on our sensor data proved challenging due to varying sensitivity ranges and faulty readings. That required tweaking the graph weights and implementing a diagnostic tool to understand the fundamental issues.

On the physical design of the robot, Alessandro pushed really hard for a base with suspensions. Inspired by the design patterns on older farming equipment, he designed a pivoting system which required minimal maintenance and extra components. This design choice worked surprisingly well, and contributed in large part to the ability of the robot to navigate bumpers and debris without complicated software routines.

An early prototype of the base of the robot with our suspensions system.

To acquire the information coming from the sensors, logging, and diagnostics, we based our software on the Robot Operating System (ROS), which provided a plethora of tools specifically designed for robotics. We ended up using ROS only up to a small fraction of its full potential — the learning curve was steep and we were on a time crunch — but it proved extremely useful for handling sensor data and the communication between modules using the publisher/subscriber architecture. We implemented the debugging/diagnostic tool in Python, tapping into ROS’s architecture, and built the GUI using the pygame library.

The computer-vision pipeline itself ran on the Raspberry Pi: the Pi handled camera capture and image processing (OpenCV) and sent recognition results to the BeagleBone Black over a simple serial link. We evaluated using a CNN approach, but ultimately opted for a lightweight preprocessing + k-nearest neighbors (KNN) classifier because it required far less training data and was easier to adapt to the real competition arenas for which we didn’t have representative training examples.

Our robot navigating the maze (our testing arena) and successfully avoiding a prohibited zone (black tile).

A shot of a monitor displaying one of the debugging tools we made. It ran real-time allowing us to understand if the robot's understanding of its environment was correct.

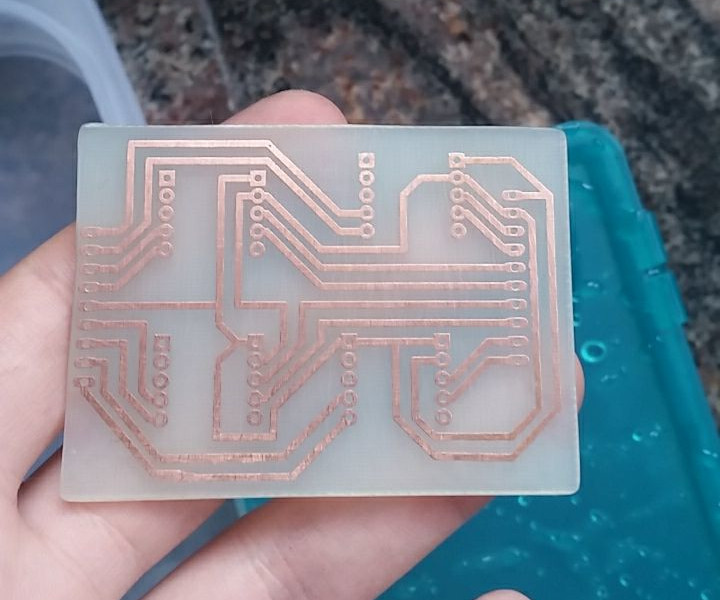

To satisfy the requirement of modularity we decided to learn how to design and prototype PCBs using chemical etching. The process started with a blank copper-clad board and involved printing the PCB design with a laser printer onto regular paper and heat-transferring the toner lines onto the copper board. We then used an etching chemical such as ferric chloride to remove the excess copper not covered by the toner. The last step involved using acetone to remove the residual toner, leaving a clean finished board.

Our custom sensors' PCB after etching.

The final product after polishing.

The specific components that were used for the robot were the following:

| Task | Component | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Main board | BeagleBone Black version C | Main logic, motor control |

| Computer vision | Raspberry Pi 2 | Running OpenCV |

| Temperature sensor | MLX90614 | For identifying the victims |

| Distance sensor | VL53L0X | High-precision sensor — I2C |

| Distance sensor | HC-SR04 | Backup sensor with low precision — PWM |

| Color sensor | TCS34725 | For recognizing and avoiding the black tiles — I2C |

| Orientation sensor | MPU-6050 | Serial communication |

| Camera | USB100W03M | USB — connected to Raspi |

| DC motors | Maxon | PWM |

| Rescue kit dispenser | Servo 9g | PWM |

The main upgrade for which we were most excited was the use of Time-of-Flight (ToF) distance sensors. A ToF sensor measures how long it takes for an emitted infrared laser pulse to reflect back from a target, giving much more precise distance readings compared to an HC-SR04 ultrasonic distance sensor. It features two modes: a single-shot mode, which produces a measurement on demand, and a continuous mode, which measures the distance at regular intervals (commonly on the order of 100 ms).

As I mentioned, this turned out to be more than we could chew. Or more precisely — we managed to build the robot in time for the competition, but the amount of testing that we managed to perform before the competition was minimal. This in turn caused many bugs to be left in the final product.

The national competition in Foligno and the European competition in Montesilvano

The 2017 national competition was organized in the town of Foligno.

I will cut this short: we did not win this competition. The lack of testing showed itself clearly, and specifically in the form of sensors issues.

The VL53L0X Time-of-Flight distance sensors, in which we had high expectations, ended up failing us. It was not the sensors themselves but rather the high-level library we used to manage them. That library — the only high-level Python library available at the time — could only read the sensors in single-shot mode using a blocking procedure. The BeagleBone’s I2C interface therefore could not handle multiple readings in parallel, and each reading was slow. Okay — each reading was only a few hundred milliseconds, but because we had 12 sensors in total the delay became critical.

Although this was not the only bug, it was certainly the main one. During the competition days we mitigated it by reducing the number of active sensors while the robot was moving and by prioritizing those directed toward the front. This, however, reduced precision and left the robot overall slow-moving.

Ultimately, we did not perform too badly at the competition. But the early rounds impacted the overall score, and ultimately we did not make it to the podium.

The venue of the competitions in Foligno.

The Rescue Maze arena used in Foligno.

A new occasion presented itself in the form of the European competition in Montesilvano (Pescara). This was a European-level competition (SuperRegional competition) which served as a middle-ground between the regional/national competitions and the main international one.

With one extra month to mitigate the issues we faced, we greatly improved on the leaderboard, finishing in second place — just behind the Croatian team, which had already qualified for the international level from their national competition (and which — spoiler — went on to win the world title in Japan).

Unfortunately, the European competition did not grant automatic qualification to the international level, but only on the condition that any spot became available due to excess capacity of the international venue, or any of the other teams dropped out.

For the month following the Montesilvano competition we had intense correspondence with the international organization to see if a spot would become available, and eventually we received positive feedback.

It was now time to prepare for the next step: Japan.

The international competition in Nagoya, Japan

Excited at the prospect of competing in Japan and representing Italy on the international stage (together with the other Italian team from Schio, which had qualified in Foligno), we started working again on the robot.

Only two obstacles stood between us and the trip. 2017 was our graduation year, and finals took place in June and early July. As soon as the exams were over, the school would close for the summer.

There was no way around the first issue: we had to split our time between graduation and the robot until the end of the finals. After the school shut down we moved into my parents’ house in Strigno and brought with us half of the lab.

The state of my parents' livingroom for the whole summer prior to the competition (my mother is a very patient woman).

Daniele upgrading one of the modules. On the right, the front panel of the robot with the logos of our generous sponsors.

In Strigno we spent a few very intense weeks: on the one hand upgrading the hardware and software, ironing out bugs and performing as many test rounds as possible; on the other hand seeking sponsors to cover the participation fees and travel costs. After all, a trip to Japan did not come cheap, especially in summer, and the school had very little disposable budget for this type of activity following many years of cuts in public funding.

Over the summer we managed to find several generous local companies whose contributions allowed us to go to Japan. In no particular order these were:

- Castelpietra S.r.l. — specializing in measurement tools in the automotive industry;

- Polo meccatronica — technology hub in Rovereto;

- Ecoopera — waste management solutions;

- TrentinoSviluppo — local agency for innovation, business, and territorial development for the Trentino province;

- Filippi — a family-run confectionery shop in Trento;

- Dr Schär — leader in production of gluten-free foods and snacks;

- Rotary Club Trento — the regional division of the Rotary Club International.

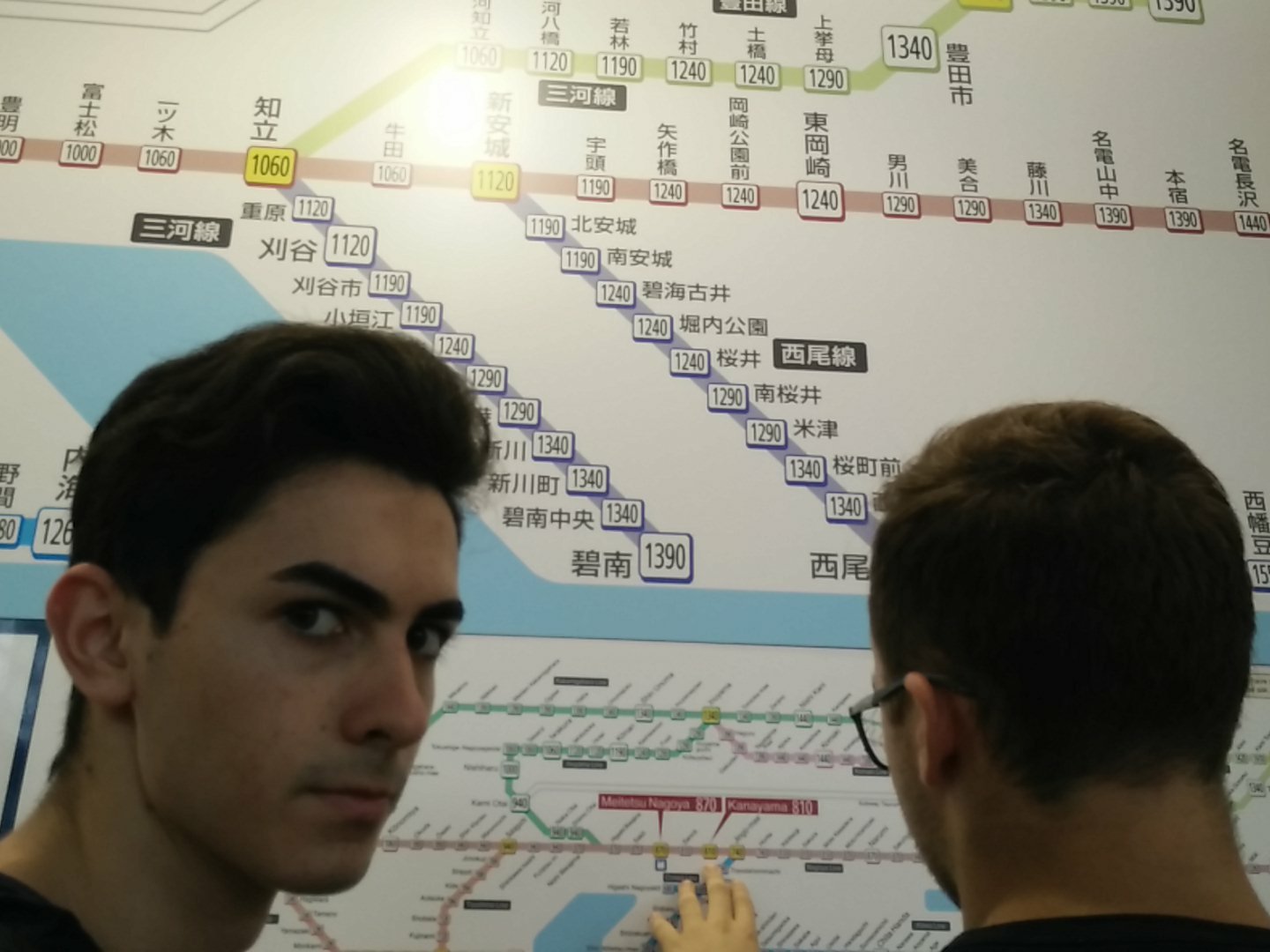

Loris and Daniele figuring the way from the airport to the hotel.

From the left Alessandro, Daniele, and myself.

Alessandro and I during one of the rounds.

The competition rounds were split among two days for the main competition, with an extra day for the “SuperTeam”: two teams from different countries were randomly matched in order to coordinate and compete against the other pairs in a new competition that was kept secret until the days of the event. With such short notice, the aim of this new competition was to test the ability to adapt and problem-solve in an extreme time crunch, as well as to work around language and cultural barriers.

During the competition days, technical interviews also took place to award the following additional prizes:

- Best Software Programming

- Best Rescue Engineering Strategy

- Best Innovation

- Best Presentation

- Best Team Spirit

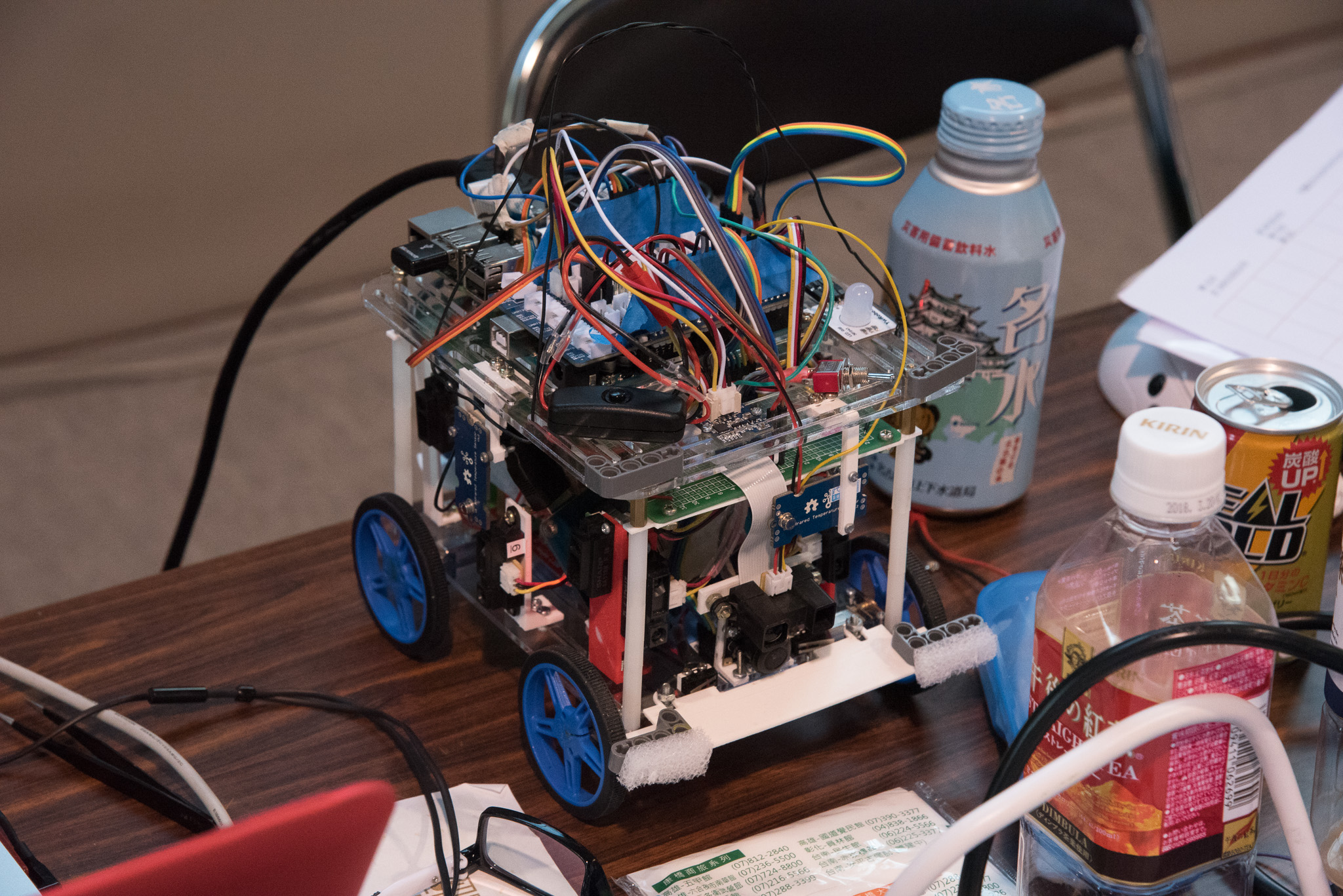

One of the other participating teams. Flying wiring was a very popular design choice.

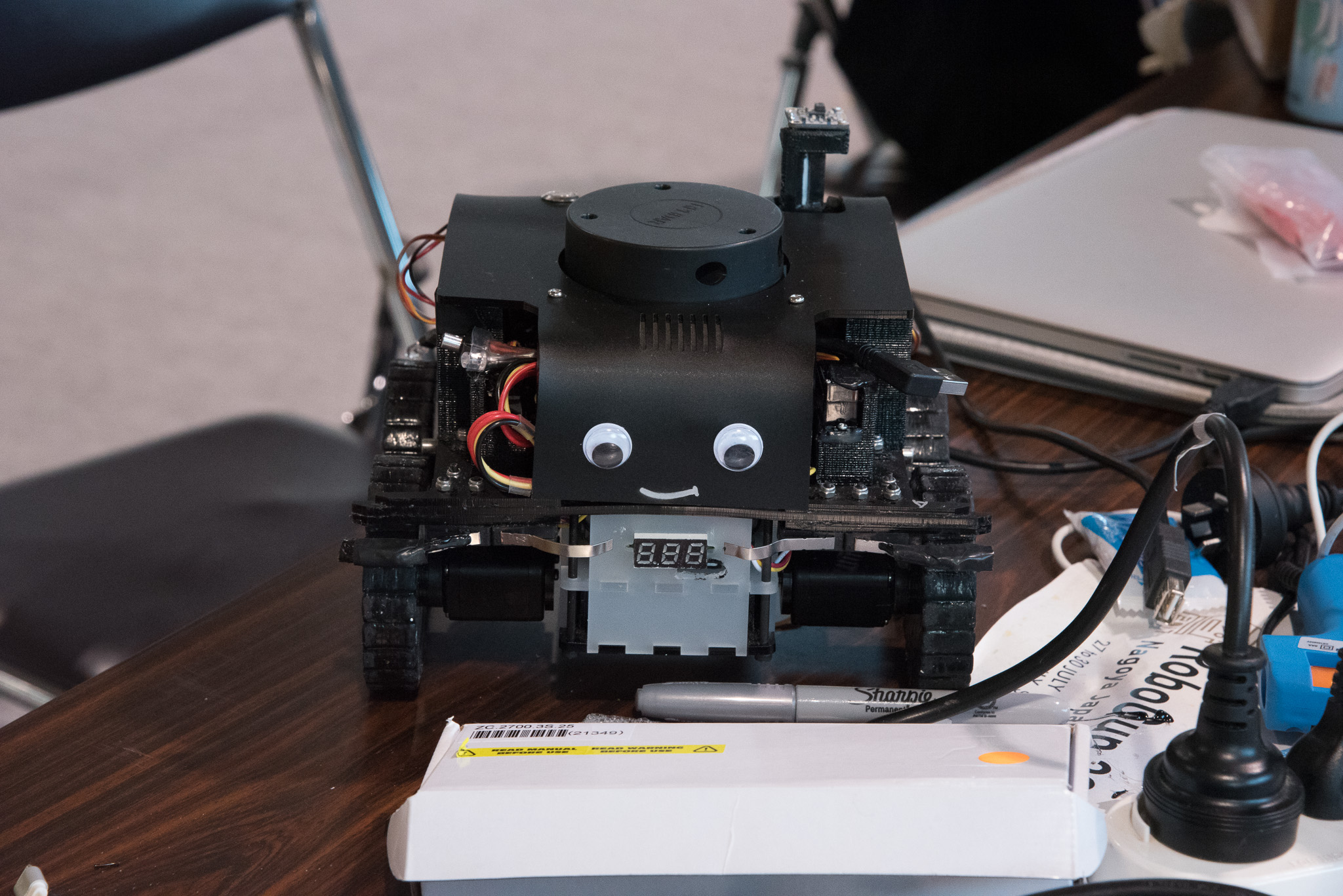

The robot of the Australian team, featuring a full LIDAR system.

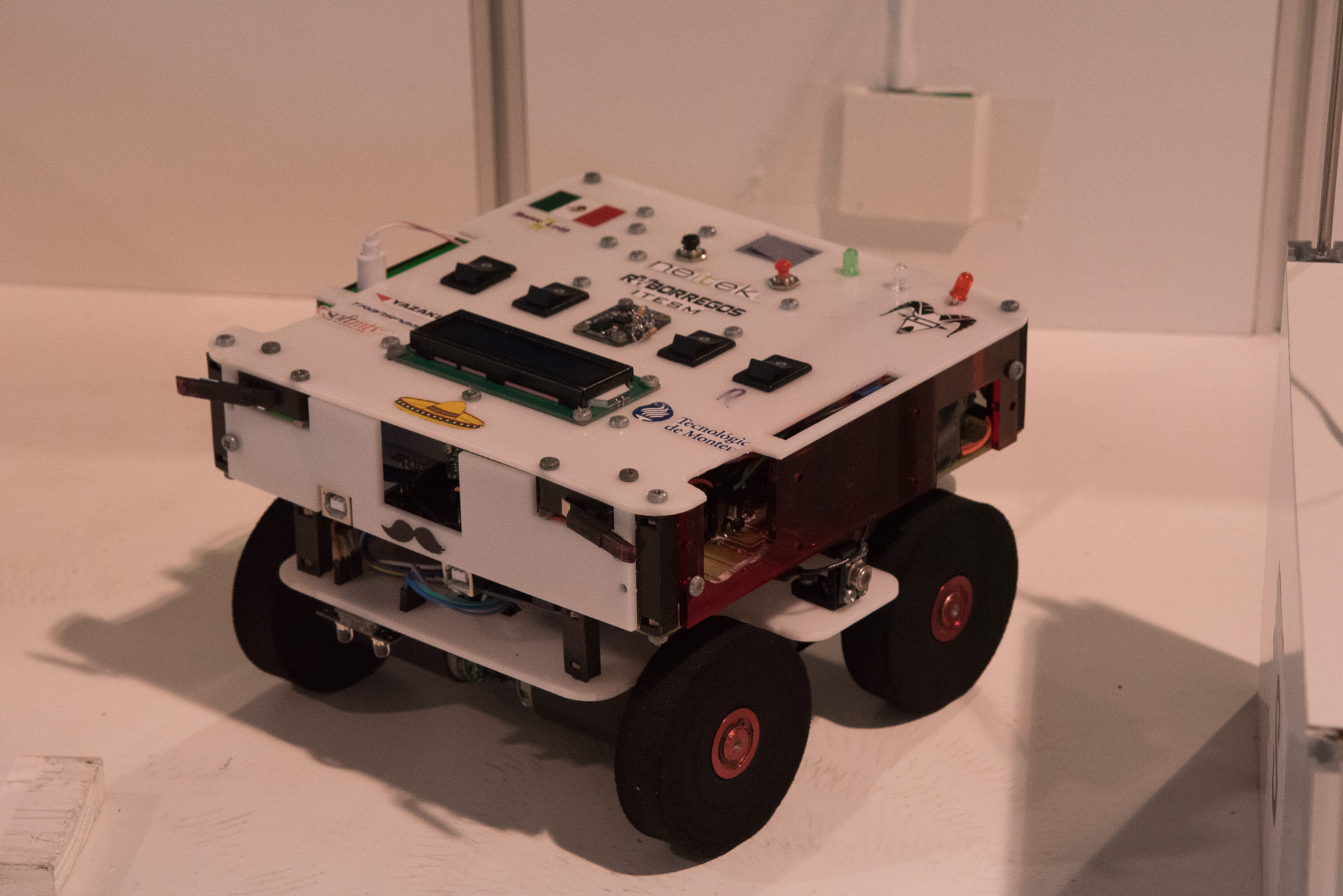

The robot of the Mexican team, built with laser cut panels.

Although our robot had many bugs resolved and the software had become more reliable, we ultimately didn’t qualify for the podium and finished around the middle of the leaderboard. Considering this was the international level of the competition, which saw the best teams from all over the world competing for a spot on the podium, this was in no way a trivial achievement.

For the SuperTeam we were paired with a Chinese team and given very little time to coordinate. We started by showing each other the high-level parts of our systems — their sensors and control heuristics and our mapping and path-planning routines — and agreed on a minimal interface so the two stacks could interoperate for the collaboartive run. Thankfully, we had brought with us a couple of bluetooth serial chips that we could use to connect the two robots. Communication was challenging at first (language and cultural differences), so we relied heavily on sketches and Google Translate. The resulting cooperation was imperfect but effective — we managed to place ourselves again around the middle of the leaderboard.

Shortly before the award ceremony, the jury informed us that our team had won the Best Software Programming prize. The award felt especially meaningful to us: the judges explicitly cited our computer vision letter-recognition algorithm and the ROS integration as key reasons for the decision, and we were genuinely delighted and proud to receive it.

The team in front of the venue.

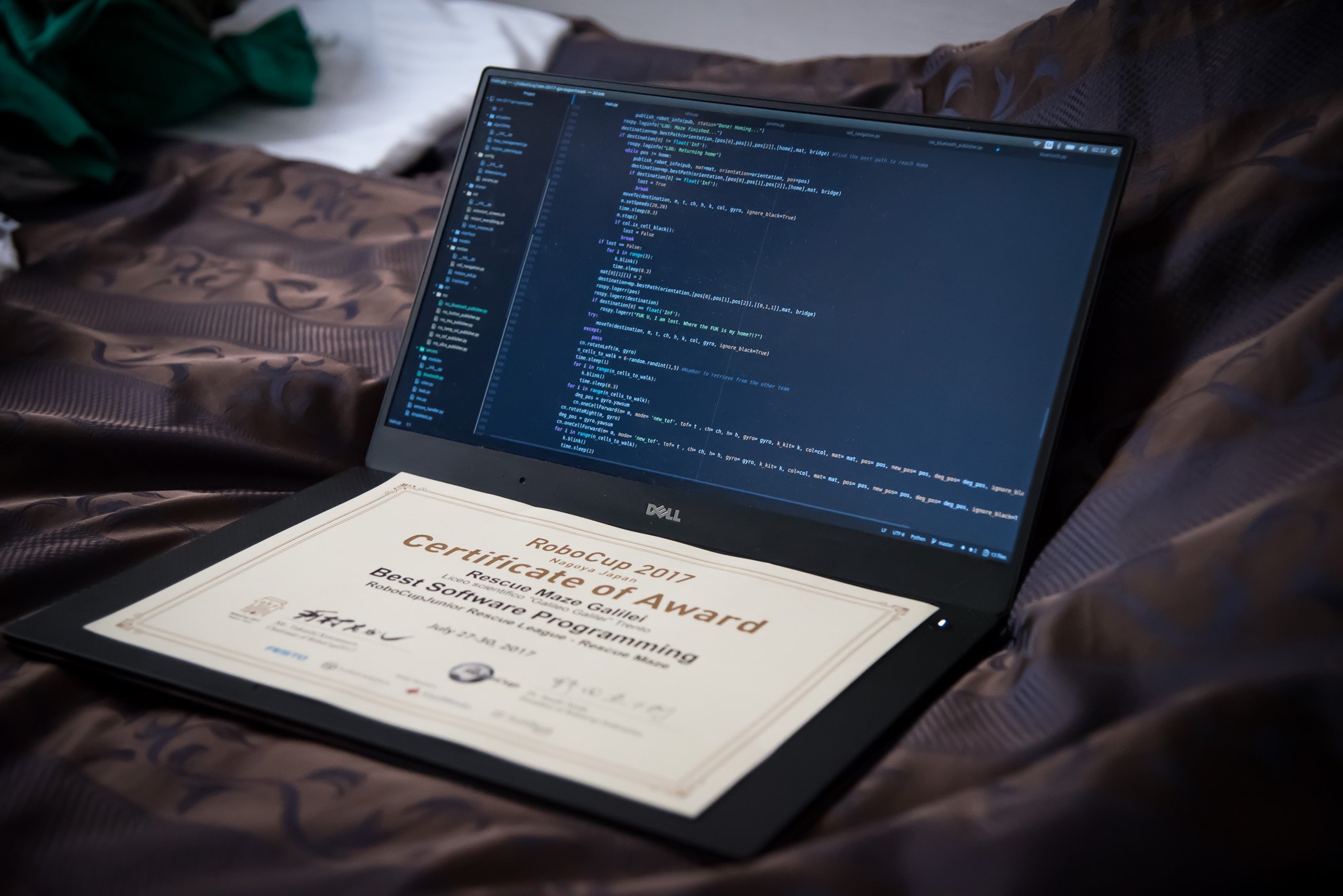

Award for Best Software, on top of my now retired XPS 9560.

Takeaways and considerations

This project left us with lessons that reach far beyond the technical stack. Building a competition robot forced us to make choices every day about what to prioritize, how to split effort, and how to persist when things broke in unexpected ways. Time management proved as important as code: we learned to break large problems into small, testable goals, to schedule focused blocks of work around exams and other obligations, and to accept that shipping imperfect but well-tested features is often better than waiting for perfection.

Teamwork was the engine that made everything possible. Each member brought different strengths — mechanics, electronics, algorithms, or a calm head in a crisis — and trusting one another to own pieces of the project let us move faster than any of us could alone. We learned to communicate more clearly and to ask for help early when in need. When something failed on the field, we debugged together: someone watched logs and tried software patches, another inspected wiring and sensors. Those moments taught us resilience, how to divide responsibility, and how to turn mistakes into learning opportunities.

Finally, competing internationally was a gentle reminder that engineering is also a cultural exchange. In Nagoya we met teams from other countries, each with different approaches, tools, and ways of approaching problems. Conversations over coffee (or charging LiPo batteries) or in the pit area expanded our toolkit and our perspective. Teamwork with the Chinese team in preparation of the Superteam challenge, dealing with a tall language and cultural barrier, was an enriching experience and one of our first true international collaborations.

Many lessons were learned along the way, and although the engineering aspects are the most evident in a project like this, I am not sure they were more valuable or enriching than the lessons in time management, PR and sponsors acquisition, humility, and teamwork.

Acknowledgments

I would like to dedicate this blogpost to two key people in our journey: Andrea Cristofori and Fredrik Löfgren. Andrea was for us a great mentor, who selflessly dedicated a gargantuan amount of time and effort to the school and to us without ever asking for anything in return. Without him there would not have been a robotics club at all. Fredrik was a great judge and organizer, always available and friendly. He supported our participation in the international RoboCup JR competition and promptly helped us with the application process once a spot opened up after the European SuperRegional competition.

Unfortunately, Fredrik tragically passed away in 2024 in an accident involving a bus in Stockholm. He is fondly remembered by all of us.

Andrea Cristofori in Nagoya, directing us from the hotel to the venue.

Fredrik Löfgren at the venue in Nagoya.